I am grateful that he wrote it for me

‘Go,’ I said to Montag, thrusting another dime into the machine, ‘and live your life, changing it as you go. I’ll run after.’

Montag ran. I followed.

Montag’s novel is here. I am grateful that he wrote it for me.

“Afterword”, Fahrenheit 451

November is drawing to an end. And it’s been a very wet November. And that can only mean one thing.

Actually it can mean many things, but one thing is for sure: it’s a fitting time of year to re-read Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, in all its moody Autumnal-Americanness.

(Did I mention it’s been a very wet November?)

They read the long afternoon through, while the cold November rain fell from the sky upon the quiet house.

“The Sieve and the Sand”, Fahrenheit 451

* * *

I had first read this book in high school (very slowly and not especially critically, as was my wont with schoolwork) as my choice of study for our Review of Personal Reading (RPR) project in Higher English. I don’t remember if I’d picked up the book independently from the school library, or if it had been recommended by the English Department, or if Dad had suggested it, but I do remember him enthusing around the basic synopsis and ending-twist, no spoiler warning included unfortunately.

However the delicious irony of reading a book about reading books being banned was intriguing enough for a book-shy teenager. I may not have read it otherwise. Indeed, now I have to stop myself telling others the synopsis when recommending the book.

My notes from that study are likely an affront to Bradbury’s novel and by extension to his memory and I dread to open them up again; alas several sub-themes and plot points, even some direct quotes I’d used, have stayed with me ever since that first reading:

‘It’s been a long time. I’m not a religious man. But it’s been a long time.’ Faber turned the pages, stopping here and there to read. ‘It’s as good as I remember. Lord, how they’ve changed it in our “parlours” these days. Christ is one of the “family” now. I often wonder if God recognizes His own son the way we’ve dressed him up, or is it dressed him down? He’s a regular peppermint stick now, all sugar-crystal and saccharine when he isn’t making veiled references to certain commercial products that every worshipper absolutely needs.’ Faber sniffed the book. ‘Do you know that books smell like nutmeg or some spice from a foreign land? I loved to smell them when I was a boy. Lord, there were a lot of lovely books once, before we let them go.’ Faber turned the pages. ‘Mr Montag, you are looking at a coward. I saw the way things were going, a long time back. I said nothing. I’m one of the innocents who could have spoken up and out when no one would listen to the “guilty”, but I did not speak and thus became guilty myself. And when finally they set the structure to burn the books, using the firemen, I grunted a few times and subsided, for there were no others grunting or yelling with me, by then. Now, it’s too late.’ Faber closed the Bible.

“The Sieve and the Sand”, Fahrenheit 451

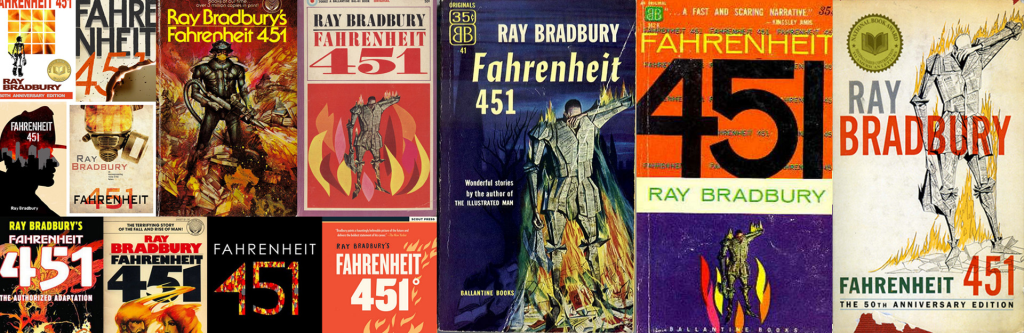

I had not read it for almost a decade following that first study. Then one birthday my sister had sent me a fiery 2008 paperback edition and my interest was reignited. Since then I have read it at least once a year, frequently taking the copy from the shelf to dip into. The more I re-read it and the more the World changes, time and time again I am grateful that Bradbury wrote it for me, and for us.

Occasionally Dad and I will discuss our mutual admiration of Fahrenheit 451, as we did a couple of Christmases ago. He asked if I had seen the film? I thought he meant the old 1966 film (directed by François Truffaut and cleverly featuring Julie Christie as both Mildred and Clarisse) but no, he was talking about HBO’s 2018 offering. This had completely slipped my radar, and I was excited to explore it! A few months later, I paid a miserable rental fee to watch the film one Saturday evening, and was bitterly disappointed. The following discusses why, and compares the film to the virtues of the book.

Recent shifts in life and in society have given me the clichéd new appreciation of Fahrenheit 451, a solemn picture of the future and of the closing of the (American) mind. Perhaps a mid-Twentieth Century Black Mirror of sorts. In thinking-through the work and reading online discussions, two interesting misconceptions have surfaced:

1. Bradbury has been labelled a science fiction writer, but always insisted he was not. It just so happens that his best-known work could reasonably be categorised as science fiction. But others of his short stories, such as The Scythe (‘Who wields me wields the World’) would counter this.

2. Bradbury was famously once challenged about the core meaning of his book, while lecturing on Fahrenheit 451 at an American college. He insisted that it wasn’t about censorship, though that is a major theme. But was he wrong? Can’t the book be about more than one thing, i.e. censorship and dumbing-down? After all, the conversations with Beatty are as terrifying as Mildred’s addiction to her television.

We are fortunate that Bradbury was so open about his work, and was happy to share the Fahrenheit 451 inspiration and creation story. The updated Introduction and Afterword are well worth a read; he describes how we would have found him in the basement of the UCLA library pounding away on the rented typewriter for eleven days to compose his novel. His characters wrote the story, he says, he merely listened to and followed them. Nine dollars and fifty cents later, his grafting and conjoining of novellas was here! The Pedestrian meets The Fireman meets Bright Phoenix. When in need of a quote for Montag to accidentally read, the author reached randomly into the shelves:

I cannot possibly tell you what an exciting adventure it was, day after day, attacking that rentable machine, shoving in dimes, running in and out of the stacks, pulling books, scanning pages, breathing the finest pollen in the world, book dust, with which to develop literary allergies. Then racing back down blushing with love, having found some quote here, another there to shove or tuck into my burgeoning myth. I was, like Melville’s hero, madness maddened. I had no way to stop. I did not write Fahrenheit 451, it wrote me.

“Afterword”, Fahrenheit 451

One problem I did find during my first reading of Fahrenheit 451 and echoed by others, is the over-descriptiveness of Bradbury’s prose. In places there are whole paragraphs of scene-painting that overbalance and interrupt the flow of the narrative. Personally I would have settled for a shorter novel, especially as Bradbury doesn’t specify a tangible place or time in which the story is set. It was also the first time I’d read a book without chapters (the story exists in three parts) and occasionally found it too spacious.

Nevertheless, his predictions were nothing short of genius. My wife began reading it for the first time recently, and asked when it had been written. Nineteen fifties, I’d replied. ‘But how did he know?!’ She exclaimed, impressed by his uncanny visions of his future, and of our present:

The front door recognises its owners’ touch and opens for them, while a visitor will be announced (‘Mrs Montag, someone’s here’).

The Mechanical Hound has its inbuilt database of respective suspects’ biochemical indexes (didn’t we voluntarily offer our DNA samples complete with all personal details to the Government when we suspected we’d contracted COVID-19?!).

The parlour has three walls of television (four if you can afford it).

There are silent air-propelled trains, earbud radios, and cameras everywhere, hovering in the bellies of helicopters.

I can’t wait to have the spidery hand that delivers butter-drizzled toast direct to your plate.

* * *

Guy Montag, Monday’s Man, grins the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. His ignorance and indulgence are well captured in the first few pages; he is good at his job, and he enjoys it. He knows that he might wink at himself in the mirror back at the firehouse, where he showers luxuriously and falls down a hole in the floor. En route home, a conversation with the girl next door shatters the thin pane of glass he’s been living behind

Wake up!

Returning home, he now cannot see his wife in the same light.

Hey – the man’s thinking!

Mildred is a warning to us all – you and I can and will become just like her; it’s as easy as switching on a Netflix series rather than picking up a book. Just give more precious time to Love Island or some celebrity show every evening and allow them to become your ‘family’ on the television walls. Soon you will forget when and where you met your spouse. How far would you go in the name of entertainment?

Seventy years after the first publishing of Fahrenheit 451, you can now download an app direct to a device that connects you with a live gameshow or reality show. Limitless laughter. Record your feelings by judging, voting, commenting, along with millions of others across the country. Failing that, one could watch an influencer recording their own real-time reactions to their first time watching some household-name media text series film / video game / TV series. How surreal that it is now acceptable to spend time watching people watching people as consumable entertainment? And when I took out the bins recently I saw an empty television box in the bin store – one of the neighbours now has a sixty-five-inch set!

On one wall a woman smiled and drank orange juice simultaneously. How does she do both at once, thought Montag, insanely. In the other walls an X-ray of the same woman revealed the contracting journey of the refreshing beverage on its way to her delightful stomach!

“The Sieve and the Sand”, Fahrenheit 451

It’s all preserved in screens and clouds, but can you imagine the beautiful manuscripts behind the glass cases of the British Library going up in flame? Did you know about the fires at Ashburnham House and that we almost never had the Beowulf manuscripts?! Some things are lost and we will never set eyes on them.

After all, it is a pleasure to burn, a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed.

So now to the 2018 Ramin Bahrani film loosely entitled ‘Fahrenheit 451’.

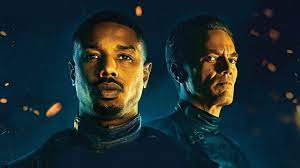

The casting was good: Michael Shannon (Premium Rush, Knives Out) gave his signature-slightly unsettling and slightly unhinged portrayal of the tortured antagonist, Captain Beatty. His performance gives an uneasy foreboding of danger, as the authority figure that becomes a law unto himself. I’d always imagined Beatty as plumper, rounder, more red-faced, as I think the book would have him, but his was good. But where was his frustrated-love of literature?

‘I’m full of bits and pieces,’ said Beatty, ‘Most fire captains have to be. Sometimes I surprise myself.’

“The Hearth and the Salamander”, Fahrenheit 451

The casting of Sofia Boutella (Kingsman: The Secret Service, The Mummy) as Clarisse McClellan was a thoughtful yet somewhat misdirected choice; Clarisse needed to be a more gentle, classic beauty, and much more innocently so as Montag’s teenage neighbour and Boutella’s visage was too mature and too exotic. However she gave an admirable performance given the direction. It would have been better if she had suddenly disappeared from the film, as Clarisse does in the book.

And of course our protagonist, Michael B. Jordan (Fruitvale Station, Black Panther), blissfully ignorant, and then later anguished and tortured. I’d always naturally pictured Montag as Caucasian with longer hair, but this was a good realisation, and genuinely did not feel like forced and passive-aggressive race-swapping. After all no description of Montag’s appearance is given by Bradbury.

Granger was played by…. Oh wait, they missed out Granger.

Mildred was played by…. Oh, they also wrote out Mildred’s story?!

Faber was portrayed by…. don’t tell me they missed out Faber!

So I gather that they didn’t trust the source material and felt they could make a better story than Bradbury? So why take away three pivotal characters if you don’t have anything better to replace them with? How would Montag complete his journey? Who would he be pitted against? Who would make him realise how empty life is, and how fulfilled it could be, and how to get there?

And so Clarisse was repurposed as a double-agent, working for the ‘EELs’ instead of a kookie kid who sits around and stares and asks and talks. Montag was never to find the arrangement of autumn leaves pinned to his door, or see Clarisse shaking the walnut tree, or studying the moon, or, very slowly, tilt his head back to taste the rain…. These natural realisations could have been beautifully shot against the urban electric lights of the world-scape scenes! It wasn’t the kids in the beetle that killed Clarisse – it was the production of this movie!

I would have dearly loved to see a faithful representation of this story on screen. They had one job to do, and that was to tell the story of Fahrenheit 451. Did they believe they could tell a better story?

One change that worked well was the infrastructure of Alexa/Siri/Google-type cameras inbuilt to Montag’s home, which of course would stop watching the resident at a word of command. This was not in Bradbury’s original, and perhaps would be more intrinsic to an adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984. However it was understated and relatable.

So why make unnecessary and avoidable changes that damage a clever story? Would they do that to 1984 and get away with it?! Call it something else, give it another title (e.g. ‘The Fireman’ or ‘A Pleasure to Burn’) or stick more clearly to the story, for goodness sake.

Beatty’s monologues would have beautifully suited the smarmy and intimidating performance we all know Michael Shannon would have dropped. The desperate state of poor Millie, poor Millie, is one that we all needed to see, especially these days, where so many lives revolve around their home entertainment and don’t realise what’s really going on!

And everyone needed to see and fear the Mechanical Hound!

I just don’t understand why film producers can’t trust the book or source that they’ve been tasked with representing on film? Were there copyright entanglements, that perhaps mean the film company may use the story idea but not the details? Faber and Mildred are a warning to us. A warning that this film skipped over.

Why change the nature of Clarisse McClellan’s feature in Montag’s journey? Why make her an informer for Beatty? It was weak and didn’t make sense. People do things for a reason, and in Bradbury’s novel, everyone has their reasons. In the film, the reasons became unclear.

The change that annoyed me the most was one that really came across as arrogant, and that was the burning of the woman in her house of books. In the story, she was genuinely gutted about losing her library, and chased the men out with a kerosene-soaked kitchen match. The film version displayed no such regret from her, but almost a smug reveal of the magic code word that somehow would setup the rest of the film.

Play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.

“The Hearth and the Salamander”, Fahrenheit 451

The film didn’t allow Montag to become wise, as in the book. Nor was it allowed to warn of the dangers of books being destroyed and banned, and of the population becoming addicted to meaningless entertainment, losing the ability to think critically and enjoy beauty. My wife pondered that it wasn’t in the films interest to decry the value of visual entertainment via screens. Worst of all, they completely cut out the two characters of Mildred and Faber – what madness drove them there? An exiled English professor must warm his frightened bones somehow, and reading through a radio earworm is the perfect hiding place:

‘Would you like me to read? I’ll read so you can remember. I go to bed only five hours a night. Nothing to do. So if you like, I’ll read you to sleep nights. They say you retain knowledge even when you’re sleeping, if someone whispers it in your ear. Here.’

Far away across town in the night, the faintest whisper of a turned page. ‘The Book of Job’.

“The Sieve and the Sand”, Fahrenheit 451

Ultimately the heart and meaning of Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 were ripped out to make way for what one can only suppose the director felt would be better ‘entertainment’. But the production clearly doesn’t understand a good story, and didn’t trust the source material enough.

Ironically, the story as told in the book wasn’t trusted enough to entertain and was dumbed-down. They tried to be too clever and changed the course of the story, removing three pivotal characters, Granger, Faber, and especially Mildred who was in some ways the essence of the novel as Bradbury’s dumbed-down victim.

The confrontation between Mildred and her friends with Guy and Faber in his ear would have been so tense.

‘Any man’s insane who thinks he can fool the Government and us.’

“The Hearth and the Salamander”, Fahrenheit 451

So many imaginative questions are pricked – how would a government ban the reading of books? How would they know who was doing it in the privacy of their home? The answer surely would be to advertise to consumers an entertainment so familial that they would actually pay to have cameras installed, so as to take part in the entertainment themselves.

A few final questions arising from my latest reading:

1. Why is Clarisse’s Uncle a character, and not, say, her Father? This would mean there were four people living next door to Montag when it could as well have been three.

2. Did Mildred kill Clarisse, perhaps accidentally? This is hinted at when Mildred suggests that Guy take the Beetle and go smash and kill things. Or did she secretly observe Montag and Clarisse talking outside and killed Clarisse out of jealousy, knowing she could blame someone else?

3. Is Bradbury’s method for the outcasts’ memorising of books lazy (‘Nothing’s ever lost’)? We could have done with more detail on how their technique for reconstructing works of literature from memory given that this is the great solution to the dystopia.

4. How did Montag know that ‘Beatty wanted to die’? And how did he know that ‘Clarisse had walked here’ (on the railroad tracks)? These leads are not necessarily helpful to the story so why include them?

Once again, I am grateful that he wrote it for me.